Eleven-year-old Azlan from Afghanistan was one of thousands of unaccompanied minors who arrive in Europe every year, fleeing conflicts in their home country or simply seeking a better life.

AZLAN’S DREAM was to join his mother Kashmala, who was travelling separately to the UK.

Greek police intercepted him as he was being transported by a ring of human smugglers.

A Greek NGO called “Smile of the Child” took care of him but he ran away twice from their shelters, desperate to find his mother. The NGO lost contact with him after he absconded for the second time, but several months later they found out that he had arrived safely in the UK and had been reunited with his mother and brother.

UNACCOMPANIED CHILDREN in the European Union submitted 12,430 asylum applications in 2013.

1,095 of them were lodged by children younger than 14 years old. Many of them are entering the EU after having lost their homes and making harrowing, life threatening journeys in order to escape war, violence and poverty. Often beginning their journeys with parents or siblings, many children are deliberately separated from family members and taken away by child traffickers or smugglers. Other children leave their home on their own initiative, fleeing a situation of abuse or exploitation. Some go missing from the reception centre in which they have been placed, or run away for fear of being returned to the situation they tried to escape when beginning their journey. Others fall victim to kidnapping, trafficking, sexual exploitation, economic exploitation, including forced donation of organs, forced labour, drug smuggling and begging.

ONE SUCH VICTIM IS AKOFA, from Togo in Africa.

Aged just 14, she arrived in France after she and her parents accepted the promises of a local woman that in return for working in a Parisian fashion boutique, she would go to school and live a better life. Instead, Akofa was made to sleep in a small corner of a kitchen, given meagre monthly rations and worked day and night without pay, and left without any means of contacting her parents back in Togo.

WHEN SHE PROTESTED, the teenager was “sold” to another family, which needed round-the-clock help with childcare and domestic chores.

“I was a slave,” says the victim of labour exploitation. “The only difference was that they didn’t buy me from my parents. But they betrayed my trust and that of my parents. I was promised education in return for my help. I knew that what was happening to me was unfair because I had a family before and knew how human beings should be treated.” After five years, police rescued Akofa from her so-called “owners”. She then spent six months in hospital recovering from health problems resulting from her ordeal.

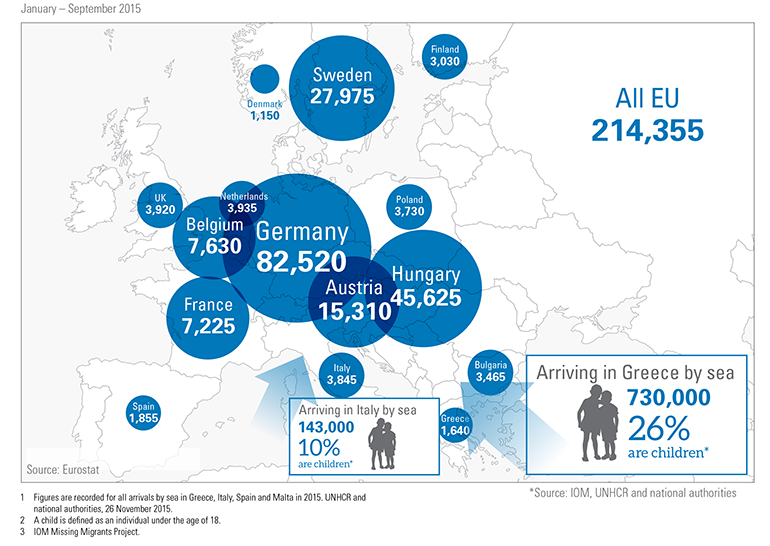

ACCORDING TO EUROPOL, the EU’s criminal intelligence agency, more than 10,000 refugee and migrant children are currently missing.

5,000 disappeared in Italy, the same number vanished in Germany, and 1,000 are unaccounted for in Sweden. In the UK the number of children who disappear soon after arriving as asylum seekers has doubled in the past year, raising fears that they are being targeted by criminal gangs, often with links to human trafficking. Europol has warned that a sophisticated pan-European “criminal infrastructure” is now exploiting the refugee crisis.

© Council of Europe – Child pictured is not related to the content of the article

© Council of Europe – Child pictured is not related to the content of the article

A WORRYING NUMBER OF MISSING CHILDREN are never found again.

60% of unaccompanied migrant children in UK social care centres go missing and are never found, according to the British Asylum Screening Unit. Up to half of the unaccompanied migrant children placed in reception centres in Switzerland, France, Belgium and Spain vanish yearly from certain reception centres, many within 48 hours of being admitted, according to the NGO “Terre des Hommes” Due to the lack of reliable information on the families, situations and realities of unaccompanied migrant children, many of them are never located once they go missing. “We must assume that many of these children and young people have fallen into criminal circles where they are forced into prostitution or their organs are removed,” said Aiman Mazyek, chairman of the Central Council of German Muslims, at a recent press conference. He called for more to be done by governments and international organisations to trace the missing minors and protect the ones who remain. “The silence in the face of so many missing persons can be heard very loudly,” said Mr Mazyek, “the refugee crisis is also a crisis of refugee children”.